Not long ago, farmers considered it a waste of money to try getting celebrities interested in agriculture. Even though the famous (and the not-so-famous) should have cared about farming, for the most part they didn’t, because they really didn’t have to. Trying to convince them otherwise was futile. Some exceptions prevailed, such as Willie Nelson and the Farm Aid forces. But overall, farming was not a cause celeb.

And neither was it a public passion. However, journalists kept an eye on it, knowing agriculture’s secret “ that is, it’s long been the second-biggest economic driver in the province and the country, and farmers are among the most respected professionals of any sector, right up there with medical personnel and emergency workers. Their stories are a fantastic and often dramatic blend of human interest, environment, community, business and globalization.

That, though, also creates problems reporting on the farm sector. It’s laden with terminology, jargon and history, so farmers and journalists can have a tough time wading through issues for readers, listeners and viewers. For their part, farmers found it discouraging when hours of explanation turned into a few sound bytes or lines of copy. Others were put off when a complicated issue was given short shrift. Conflict drives the news, and while that can encompass conflicting ideas rather than people, farmers didn’t like being pitted against the other side, whatever it might be. They grew suspicious of the media’s motives, and the chances for dialogue became limited.

Thankfully, that’s changing. Farm groups have realized that communicating with the public is not an option “ it’s compulsory, and the media is still a vital conduit for reaching Canadians. Farmers depend on public support for many matters, such as policies involving land use that help them keep farming. So tough as it is sometimes explaining themselves, approaching media and responding to queries, they’re committed to it, and to employing professional communicators to help.

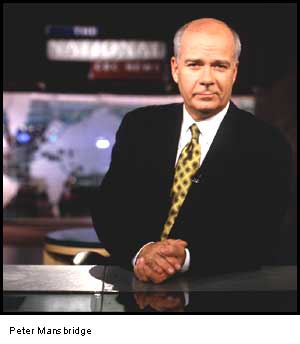

The latest example of this social construction effort occurred March 21, when 400 or so members of the Grain Farmers of Ontario, sponsors and the media filed into the London Convention Centre to participate in what the grain farmers call their March Classic. This is a professional development meeting of sorts for producers, as well as a two-way exchange of information with the podium guests who this year included CBC mainstay Peter Mansbridge and media personality Kevin O’Leary.

Agriculturally, the timing for such an initiative is and was perfect. Grain prices are up, last fall’s harvest last was excellent, demand is strong and optimism is high. Consumers’ focus has shifted to local food, while at the same time global hunger is on everyone’s mind, as are other matters that directly involve agriculture such as health and the environment. Journalists such as Mansbridge want to know what’s on farmers’ minds, and farmers need the media to help them reach the public.

Mansbridge gets it. Most people believe he’s a downtown Toronto guy, but the truth is he drives there daily from Stratford, and takes in a lot of farm scenery along the way.  He says CBC has tried to tell more farm stories over the past couple of years, and I certainly sense it on programs such as The Current, whose host Anna Maria Tremonti gets it, too. Maybe a farm story doesn’t appear every day on either her show or The National, but at least it’s on their radar screens.

In London, Mansbridge told the partisan audience to keep pitching stories. Put together a case for something that needs to be explained, he said. Tell “people stories.”

Given the public’s interest in and ignorance about agriculture, there’s no shortage of things that need explaining. So maybe the future of farming’s relationship with the media and its leaders is as promising as the future of farming itself.